Australia pulls out of Afghanistan

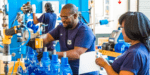

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has declared Australia will withdraw its remaining 80 troops from Afghanistan by September, marking the end of its longest involvement in a war. This follows President Joe Biden announcing the United States will leave Afghanistan by September. The path to this point has appeared inevitable for years. Ten years ago, journalist Karen Middleton highlighted the futility of the counterinsurgency campaign in her aptly-titled book, An Unwinnable War. High hopes dashed Back in 2001, it all seemed so different. Only weeks after the September 11 attacks, Australian special forces deployed to southern Afghanistan alongside US, Canadian, British and other NATO troops to defeat al-Qaeda, who was hosted by the then-Afghan government, known as the Taliban. After dusting off their boots and leaving in early 2002, Australian forces were drawn back in 2005 with a special forces task group. This was followed by an engineering reconstruction task force that over time morphed into a mentoring task force, intended to help the Afghan national security forces establish law and order. But without a clear strategy for effective governance and widespread corruption, the Taliban returned with a vengeance. The mentoring created opportunities for so-called “green on blue” attacks, which contributed to the deaths of a number of Australians. By 2014, 41 Australian soldiers had been killed. Many understandably wondered: was it worth it? Australia’s niche approach Australian politicians and policy makers were always risk-averse about the commitment. Eager to avoid casualties on the scale of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War (where 500 Australians were killed), successive governments opted to make niche contributions that relied on critical support and leadership from US and other allies. But never wanting to manage everything itself left Australia vulnerable. For example, Australia handed detainees to Afghan authorities who, soon enough released them. Some of these, it appears, ended up fighting against Australians again. With special forces, in particular, undertaking rotation […]