The hidden agenda of royal experts circling The Crown series 4

- Giselle Bastin, Associate Professor of English, Flinders University

The recent outcry from royal biographers about the accuracy and fairness of series 4 of The Crown taps into narratives that have surrounded the field of royal life writing since it emerged in the early 20th century.

There has been much hand-wringing by (royal) trainspotters, biographers, journalists and even Britain’s Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden and the actor who plays Princess Margaret, Helena Bonham Carter, about the accuracy of the Netflix series written and produced by Peter Morgan.

Criticisms of series 4 have ranged from historical inaccuracy (the Queen being wrongly dressed for the Trooping the Colour; Princess Anne’s horsemanship) to a propensity to flesh out the narrative with half-truths and downright falsities. (For example, the suggestion that Charles and Camilla remained an item all the way through his marriage to Diana, and the idea that Prince Philip gave Diana a veiled threat about what could await her if she didn’t play by the script.)

One royal biographer, Hugo Vickers, has been so incensed by The Crown’s playing hard and fast with the facts he’s sprung to action and released his own book devoted to fact-checking it.

In addition to criticising the biopic’s misrepresentation of royal lives, the show’s detractors express concerns long aired about popular history — that an admiring and gullible viewing public will assume the program is factual and treat it as real history. The public, it is implied, need protection from fake news turning into fake history.

Critics of The Crown profess to have the royals’ best interests at heart because the royal family is not prone — at least it wasn’t before Harry and Meghan — to going to the courts or on the public record to defend itself. The Windsors, they imply, are being subject to unethical treatment and are also in need of protection.

Peter Morgan and Robert Lacey (a leading royal expert consulting on The Crown) have been open about the program’s blending of fact and fiction. Netflix has announced there is no need for it to carry a disclaimer about efficacy or accuracy. People will know it’s drama, they’ve said, so move on.

I would contend there is a lot more going on than first meets the eye with these debates about The Crown’s legitimacy and accuracy. What we are witnessing are discourses that surround notions of who has the legitimate right to talk about royal lives.

In this, the field of royal biography is unique. It is tied implicitly, and often explicitly, to the systems governing the royal houses, and derives meaning and stature from its relative proximity to the locus of royal power — the monarch and inner circle of royal members and their senior servants.

In the case of current criticisms of The Crown, the chorus of disapproving voices is sending coded messages to the royals (and their royal handlers) about their social and professional suitability to qualify for the holiest of holy grails: to be the official biographer of Queen Elizabeth II upon her death.

They may have missed out on the riches and splendours of co-writing and advising on The Crown, but they’ll scramble cheerfully to secure their place in the royal firmament.

Touching ‘sore places’

In the early 20th century, a culture of royal life writing developed that saw an intricate interplay between palace courtiers and the biographers who were screened, vetted, and given (or not given) access to the details of royal lives. Royal biographers commissioned to write the official or approved biographies of the monarch entered into a tacit agreement to abide by the codes of deference and discretion. In this sense, they came to resemble the royal courtier, with all the trappings, grace, favour, honours and financial reward this role bestowed.

Indeed, royal biographer John Wheeler-Bennett cautioned those who would enter the fold it was something “not to be entered into inadvisedly or lightly; but reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly and in the fear of God”.

The culture of royal biography arguably began with royal courtier Lord Esher’s recruitment of Etonian school master A.C. Benson to help him edit Queen Victoria’s vast piles of correspondence.

Historian Yvonne M. Ward has charted how 1st Baron Stamfordham, Private Secretary to Queen Victoria and later to King George V, issued warnings to Esher and Benson that some of the queen’s letters were not to be made public.

They were of “no importance historically and would only supply matter for gossip and possibly ill-natured criticism”.

Esher brought in high-ranking friends to help edit Benson’s choices and to make especial note of “anything [that might] slip in which can give pain or offence”. One such friend assured Esher he “had kept a keen look-out […] for references or quotations that might touch sore places”.

As the century progressed, senior palace officials designed the template supposed to be followed to this day, setting the tone for how the royals should be represented on the public record. The rewards of access to the Royal Archives at Windsor, to the sacred spaces of the royal court, and the bestowment of status in the form of honours and titles awaited those who toed the line.

For those deemed to have broken the codes, social, professional and economic consequences quickly followed.

Sacred and not to be pried into

Royal biographer Jane Ridley, for instance, has shown the challenges met by Sir Sidney Lee (real name Solomon Lazarus Lee) after he was commissioned in the 1910s to be official biographer of Edward VII (Bertie).

According to Ridley, Lee wanted to exercise autonomy in his treatment of his royal subject; he also wanted to control the publication of the biography itself. Most of all, Lee did not comply with the gentlemanly codes of the royal court: “[t]he feeling against Lee was charged with anti-Semitism” and he was denigrated as a “Jew who is out for money”.

Despite his official biographer status, Lee was obstructed at every turn. Senior courtier Sir Arthur Davidson announced it would be impossible for Lee to “run riot amongst [the] chaos of the late King’s letters”. Sir John Fortescue, Keeper of the Archives, “did his best to be unhelpful […] ‘I have always treated [the royal papers] […] as sacred and not to be pried into’”.

Another eminent courtier, writes Ridley, obstructed Lee at every turn, responding to a request to see Bertie’s diaries by saying “there are no diaries and if there were the King said no one should see them!” The palace made Lee’s task impossible achieving the aim of “making him write a hagiography”.

Lee had misunderstood the tacit agreement that the biographer is supposed to act as an extension of the royal courtier, playing his part (and the use of the masculine “he” is relevant here) in protecting the privacy and reputation of the court.

This was nowhere more apparent than in denunciations of the royal life writer who preceded Peter Morgan for special criticism and ignominy: Andrew Morton, author of 1992’s Diana: Her True Story. Morton, a tabloid journalist who went to a comprehensive school, was not deemed to be of the right character or background to be the author of royal stories.

The jilted ratpack

Before Diana’s commissioning of, and collusion with, Morton became known, he bore the brunt of fury from journalists, biographers and establishment figures.

They could not believe a royal biography would air so much “dirty laundry” — and, to them, false dirty laundry — in public. Figures such as Lord McGregor, chairman of the Press Complaints Commission, Sir Max Hastings, editor of The Daily Telegraph, Sir Peregrine Worsthorne , columnist for The Sunday Telegraph, and Sir Arthur Nicholas Winston Soames ), British Conservative Party politician, were astonished by Morton’s unsanctioned act of lèse-majesté.

Unaware Diana had shaped the content of Diana: Her True Story herself, the royal court granted tacit approval for its supporters to go out and champion their cause. Morton notes in his postscript to the 1993 edition of the book that there were many in royal circles who “were keen to shut [me] away in the Tower of London”.

After Diana’s collusion with Morton became known, she became the one accused of breaking the codes of royal discretion and secrecy. As Tina Brown wrote, “the rat pack felt jilted. Their pin-up girl had bestowed her favours elsewhere, handed the ingrate freelance Andrew Morton access his colleagues had been denied”.

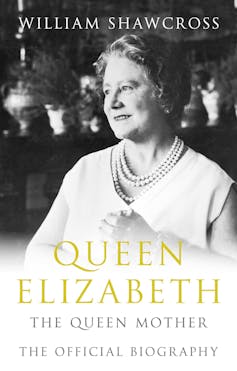

By 2009, the royal court wrested back control of the royal narrative with the commissioning of William Shawcross’s official biography of Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother. Shawcross managed, in over 943 pages, to tell the reader practically nothing whatsoever about the private character of his subject. His biography manages not only to avoid sore places, but to sketch a royal world where such places barely exist.

Honours and prestige

For those royal storytellers who abide by the rules, reward comes in the form of financial benefit along with awards and honours.

In the early-mid 20th century, it was normal for official biographers to receive the Knight of the Grand Cross. These were later downgraded somewhat slightly to lower honours (unsurprisingly, one was awarded to Shawcross).

Similarly, the withholding or downgrading of honours has been used by the palace to express disapproval in cases where biographical indiscretions have occurred.

Kenneth Rose, a biographer of King George V , long felt he had compromised his chances of receiving honours because he addressed the sensitive topic of George V’s role in turning down the Russian Tsar’s request to seek sanctuary in Britain during the first world war.

According to an anecdote told by Hugo Vickers, Rose was informed by the Queen Mother’s private secretary that his chances of an honour had “just floated down to 20 to one!” and that he would be awarded a mere Commander of the Order of the British Empire) instead.

Royal biography evolved to become, in every sense, a “gentleman’s sport”, with all the intonations of class, gender inscription, social connection, networking, and appropriate “amateur” status this phrase implies.

One simply cannot be seen to be in it just for the money, as we saw in the criticisms levelled at Lee and Morton. Yet, economic capital is contiguous to royal access, and vice versa.

Peter Morgan, despite ticking some of the boxes that qualify him to be a suitable “gentleman” biographer (he went to a couple of seriously posh English public schools, although neither were Eton, and went only to the University of Leeds), has overstepped the rules by making too much money out of the royals.

Pleasing the palace

The chorus of disapproving voices declaiming Morgan’s approach are angling for the biographers’ holy grail and seeking to protect and promote their own lucrative market share.

Morgan’s The Crown is big business. So was Morton’s book (and so, interestingly, was Martin Bashir’s 1995 BBC Panorama scoop interview with Diana, now the subject of an inquiry as to whether Bashir tricked Diana into granting it). The voices of detractors seem to grow louder in direct relation to the size of the financial rewards royal writers reap.

It is notable that when a swathe of not very well-known, low-budget and low financial yield television biopics about Charles and Diana (and Charles and Camilla, Andrew and Sarah, and Princess Margaret), such as The Royal Romance of Charles and Diana 1982 and Whatever Love Means, were released throughout the 1980s-2009, barely a murmur was heard about their accuracy or ethical imperatives.

Simply, they hadn’t made enough money nor been seen by large enough audiences in need of protection from false histories.

Similarly, debates about the first three series of The Crown were relatively muted compared to the attention series 4 is attracting. The reason may well be that the royal biographical community has started to realise a relative interloper has landed the biggest golden goose of all time.

Meanwhile, Morgan’s royal storytelling is offering some serious royalties in return, which allows him to cheerfully ignore the unofficial rule that biographical representations of the royals need to be acts of tactful omission and discretion rather than full-scale re-imaginings of life behind palace walls. He might even point out that earlier royal biographies were made up of just as much fiction and fantasy as The Crown.