These countries have the highest minimum wages

Minimum wages offer a route out of poverty, but they aren’t without controversy.

Minimum wages offer a route out of poverty, but they aren’t without controversy.

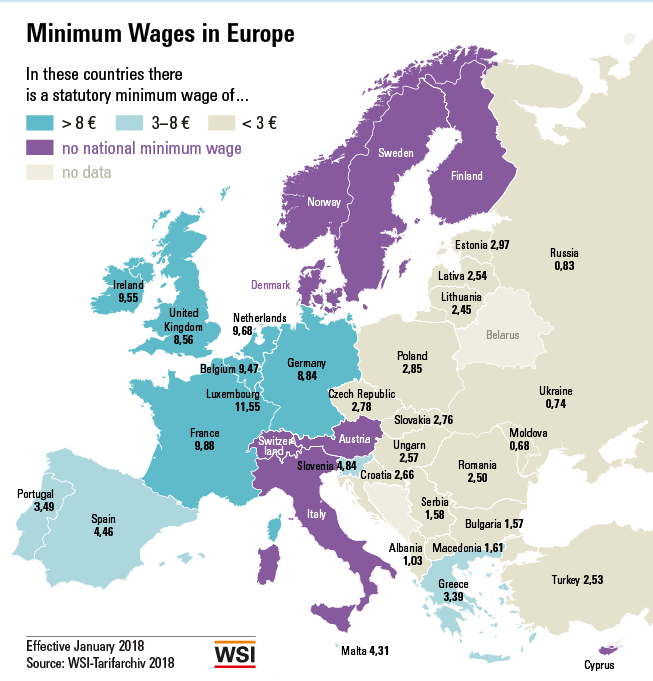

The answer is Australia or Luxembourg, according to data from Germany’s Wirtschafts-und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut (WSI), which compared pay in different countries on a purchasing-power basis.

The hourly rate in Australia yields the equivalent of 9.47 euros (US$10.78) of purchasing power, according to the report, almost six times that of Russia’s, which is worth only 1.64 euros ($1.87) in purchasing power terms. European nations made up the rest of the top five; while Brazil, Greece and Argentina were among the lower earners.

Supporting low-paid workers is a key objective for governments around the world, particularly after the financial crisis exacerbated inequality in many countries. While minimum wages offer one route out of poverty, they aren’t without controversy, often sparking politically charged debates and generating headlines.

Recently, Spain’s government said its minimum wage will jump by 22% in 2019, the biggest annual increase in more than 40 years, while French President Emmanuel Macron said his nation’s threshold will increase as well. Even in Australia, which has one of the highest levels, there’s tension between the Fair Work Commission, that sets the rate, and the unions who want more.

Those in favour say businesses have a responsibility to pay their workers enough to live on, while those against argue that a high minimum wage destroys jobs and hampers entrepreneurship. A report earlier this year by the Institute for Fiscal Studies warned that a rise in the living wage could expose more jobs to automation.

Academic studies have been mixed, calling into question long-held ideas that minimum pay thresholds lead to job cuts and fewer hours offered to employees, while also harming small businesses and pushing up prices.

“Thirty years ago, most economists expressed confidence in surveys that minimum wages had a clear negative impact on jobs. That is no longer true today,” Arindrajit Dube, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst said in an NPR podcast. “The weight of the evidence to date suggests the employment effects from minimum wage increases in the US have been pretty small; much smaller than the wage increases.”

In reality, many minimum-wage earners in developed nations work in the service sector, where it can be easier to pass pay increases on to customers via higher prices. And some companies don’t mind paying more because it lowers staff turnover, lessening outlay on recruitment and training.

Even so, there’s regional variation. In the US, the threshold varies by state, with some areas planning to boost their minimum wage to as much as $15 an hour. Cities tend to be where pay levels rise faster, because consumers can tolerate higher prices.

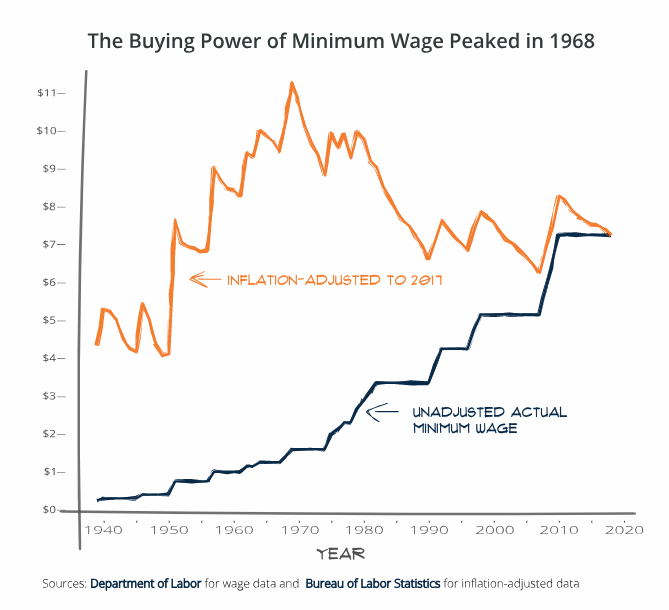

The cost of living also makes a difference. While the absolute level of pay in the US has risen in the past 50 years, workers are poorer because increases haven’t kept pace with inflation.

There’s still some way to go in researching and exploring the effects of minimum wages and their impact on the job market. Keeping track of the evolution of these thresholds relative to median wages may offer a guide to how much they can rise without leading to visible job losses, but most researchers agree that more work is needed.

“The minimum wage has a much bigger bite in lower-wage areas,” Dube says. For him, it’s about keeping a close eye on the data to locate the “sweet spot, beyond which it may not be a good idea to increase further”.