What is degrowth?

- a radical economic theory born in the 1970s.

- It broadly means shrinking rather than growing economies, to use less of the world’s dwindling resources.

- Detractors of degrowth say economic growth has given the world everything from cancer treatments to indoor plumbing.

- Supporters argue that degrowth doesn’t mean “living in caves with candles” – but just living a bit more simply.

How do we save our planet? Some economists believe the only way is to radically scale back our global consumption of resources.

This is a key premise of degrowth – a political and economic theory that is gaining traction as fears grow over climate change. But is it workable?

What is degrowth?

Degrowth broadly means shrinking rather than growing economies, so we use less of the world’s energy and resources and put wellbeing ahead of profit.

The idea is that by pursuing degrowth policies, economies can help themselves, their citizens and the planet by becoming more sustainable.

Practical degrowth actions might include buying less stuff, growing your own food and using empty houses instead of building new ones.

Degrowth as a term was coined in 1972 by Austrian-French social philosopher André Gorz, according to the website Degrowth.info. As a movement, degrowth started to take off in the early 2000s, according to media platform openDemocracy. Modern degrowth protagonists include French economist Serge Latouche, who argues that society’s current model of economic growth is unsustainable.

Why does Degrowth matter?

Government policies have focused on growing and expanding economies ever since.

With increasing awareness about climate change, the degrowth debate has accelerated.

If economic growth continues to be the default goal, it will lead to climate catastrophe, the argument goes, with no hope of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

It seems to be no coincidence that global warming caused by humans started around the 1830s, scientists believe, when the world’s first industrial revolution was at its height.

The solution is essentially to move away from the assumption that growth is good.

One of the things degrowthers would like to see is the end of gross domestic product (GDP) being used as a measure of economic progress, notes The Conversation. GDP measures an economy’s entire output of goods and services.

Degrowthers would like to see the end of GDP being used as a measure of economic progress.

What are the experts saying?

There are plenty of opponents to the degrowth theory. News and opinion site Vox argues that economic growth is what’s given the world “cancer treatments, neonatal intensive care units, smallpox vaccines and insulin.”

Freedom from poverty, indoor plumbing, electricity and longer life expectancies are other gains – the list goes on.

One of Vox’s counter arguments to degrowth is that many countries have shrunk their emissions while also growing GDP. They’ve done this using technologies like renewable energy.

Another argument is the impracticality of poor countries developing “up to a certain level of prosperity” and then stopping, while rich countries scale down to the same level.

“Who gets to decide which goods and services people choose to spend their money on?” Vox asks. There’s also the inconvenient truth that most carbon emissions in the coming decades will come from newly middle-income countries, like India, China and Indonesia, rather than rich countries like the United States.

Degrowth supporters also have compelling arguments.

The Conversation quotes Sam Alexander, a degrowth advocate and research fellow at the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute at the University of Melbourne in Australia. He says degrowth “doesn’t mean we are going to be living in caves with candles”. Instead, it might mean people in rich countries changing their diets, living in smaller houses and driving and travelling less.

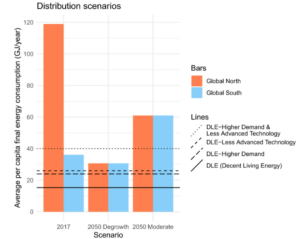

“It is important to clarify that degrowth is not about reducing GDP,” says Jason Hickel, a University of London academic, “but rather about reducing [energy and resource] throughput.”

While openDemocracy points out that, one way or another, “a different kind of economic structure is needed for an ecologically constrained world”.